Maintaining the Ledger

Published by Singletrack. Available in text and audio.

‘Do you have access to a gong? The start line needs one. That, or an antiquarian pistol’.

Peter Munnoch said no.

‘Do you think it would be reasonable to use a flare gun instead, and if so do you have one?’

‘No and no.’

Peter thought on the matter.

‘What about the potato cannon? I don’t know if it's working or if it exists anymore. I suspect my Dad will hate the idea’.

‘I haven’t seen it in twenty years’.

‘He will be sheepish about setting it off in the square’.

‘I remember it blew a hole through a wheelbarrow at sixty paces. Although that wheelbarrow was quite rusty.’

A few days later Ken Munnoch, Peter’s father, sent me a photograph of an approximately cylindrical object of curved metal and plastic connected by bolts and a single insulated wire.

‘Is that a land mine?’

It was an airbag.

So it was that on the knell of 10am on the first Saturday of August, the airbag of a Vauxhall Corsa was deployed on the village green as the Townhouse bells pealed and Derek Burns unfurled and lowered the starter flag. The bag shot skyward, the saltire dropped, and runners and riders surged forward from the gates of Culross Palace.

The Hanna-Barbera Productions crew took up the commentary.

“And now, here they are! The most daredevil group of daffy riders to ever whirl their wheels in The Culross Invitational, competing for the title of the West Fife Villages’ Wackiest Racer! First is Adam Boggon, leaping ahead with a raised Gonzo fist – every inch the young Hunter S. Thompson, if Hunter Thompson were a boy scout who couldn’t tie knots. He seems the only rider to realise that the detonation, bells and flag drop at the appointed hour indicate the start of the race. The rest of the field stand gawping. What are they doing? At last comes Alison Knapman chuckling inanely. Then Hannah Boggon, fresh from her 5am reveille at a Highland religious retreat. On comes her sister Emma, her jaw set, determined to make up for missing the race last year while fiddling at her local Fish Festival. Then there’s ingenious inventor Christine Boggon in her Convert‑a‑Bike, powered by electricity and the tugging of a small black dog. Now another cousin whose father scolds ‘helmet fastened James!’ Oh! Here’s Laura Douglas, who this year forswore her usual whole-body gold paint job, to the frustration of certain spectators. Manoeuvring for position are Janice and David Boggon, Julie Geyer, Camilla Garrett-Jones and Katie Smith, riding for two on her Bulletproof Bomb. Lurching along are Mira-Rose Kingsbury Lee and Rachel Niesen, the Gruesome Twosome. And right on their tail are Jessica Lee and Mehdi Sharifkazemi, jogging along in their Army Surplus Specials. And there are the Genesis Chug-a-Bugs with Donald Waters and Peter Munnoch. Sneaking along last on their Mean Machines are those double‑dealing do‑badders, Rob “Dastardly” Jenkins and his snickering sidekick, Chris Card — and even now, they’re up to some dirty trick! And they’re off!”

Val Burns spoke for the bewildered villagers

‘Are they just doing this all day long?’

Diane Mackenzie, sidelined this year by injury, replied: ‘They generally do. They lap’.

The Culross Invitational begins at the Palace at 10am, ends at 5pm and comprises 14-kilometre laps of a fixed course. Laps are tallied in the race ledger. The winner is the person(s) who complete the greatest number of circuits within the 7-hour period.

From the Palace the peloton rattles over the cobbled section – Sandhaven, Back Causeway, the Mercat Cross and Wee Causeway. Strynd Vennel connects to the Embankment, which riders follow along and across a railway line to trails laid on a lagoon of coal ash. Invitees recross the tracks for a dark way through Valleyfield Woods where nettles reach and sting. Out of the woods to a strip through Shiresmill leading through fields of barley. Riders press on to Balgownie Wood where bark way and wetland give on to an avenue of beeches. After that single track wires behind Kirkton Farm to the edge of Devilla Forest where packed gravel sprays across the main road to a narrow path by an old plague grave. Grass whirrs then under tyres down the Wallace Spa, a flash and scratch of brambles and oddly cambered fast descent. Wheels find embankment again by the seawall and pass the pier, cross the green, re-rattle the cobbles and find the green side gate to the garden of my childhood home where on a table rests the ledger to which riders apply their names and tally.

The first lap is sociable, the group moving at the pace of the slowest rider. This year there were 27 including two runners but not including three dogs. Most detoured to prod a 17-metre long fin whale carcass which had washed ashore before turning their attention to plates of scones and gingerbread. These pleasantries having ended, the racing began.

At the inaugural, the competitive element took a back seat. Laps were interspersed with long periods of lolling, drinking tea, and eating. Riders were called to set out on laps together. Numbers dwindled through the day until some time after 4pm when Peter and I realised that if we didn’t bolt we would not complete our fourth before the cutoff. We got round with moments to spare. Others were too slow. No fourth lap for them.

This year things were different. Lycra bodysuits were widespread, wraparound sunglasses de rigueur, and high-end gravel bikes formed a sleek portion of the field. No bugles to announce the departure of the pace setters this time, only the muffled shuffling of Rob’s clip-in shoes on the moss, Chris’ snickering, and the scrape of the side gate. Thank God for that creak – those sneaks.

The function of the Invitational is to keep relationships in repair. Lives pass and change, and mine has moved around. Inviting friends from childhood and those made in St Andrews, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Melrose, Inverness, Kirkwall, Moshi, Kampala, Fajara, London and Boston to the village once a year is an expedient means of concentrating forces and of communicating to those who cannot be there: I would that you were.

The event runs over three days. Guests mass at the Red Lion on Friday evening to sample the pub menu (unchanged in twenty years on account it being un-improvable) and fortify themselves for Saturday racing. The garden party follows the Invitational and proceeds until the last raconteur loses their audience to a polite excuse. On Sunday morning campers and lodgers breakfast and walk the village.

Riding now, memories came back from the inaugural. Arriving to set up and with my Mum responding to a road traffic accident on the road to the village (the driver, shaken, cried ‘My name is Elizabeth and I am guilty’). Of Elaine Brewster, who did not ride but who attempted to claim a certificate for eating cake. Of Donald Waters’ attempt during the garden party to persuade Patrick O’Hare that his eustachian tube dysfunction had a psychological cause. Of sunlight bright into evening. Of good tiredness. Of waking a little after 4am on Sunday still so giddy I could not sleep and rolling along with it, smiling.

This year demand increased. Some travelled hundreds of miles. The word went forth for spare bikes.

‘For the un-wheeled, any size or shape of hardtail, full-suspension, gravel, hybrid, or downhill bike will do. Even a unicycle, provided deep enough tread. We’re not picky. I believe my parents’ touring tandem would thrive on the course but the suggestion was robustly vetoed’.

The approach of indiscriminate bulk bore fruit – we got far more bicycles than required. The Steering Committee mused on Joe Stalin’s observation that ‘In the end, enough quantity becomes quality’.

One policy challenge concerned the use of electric bikes. Race terms stipulated that riders could not compete on e-bikes absent a registered disability. This provoked hostility and was ignored by several entrants, including my own Mother. The following summer a heated late night meeting of the Steering Committee agreed that electric bikes may be used without a doctor’s note provided the race ledger record an (e) beside the rider’s name and an asterisk beside their final tally.

Competition is central to the rearing of children in the village. Peter, my brother Daniel and I duked it out at the Culross Gala high jump on the village green as teenagers. Encircled by a slow-clapping crowd we usurped the heights, flopping onto a gym mat which offered about as much forgiveness as a packet of ham. No necks were broken, somehow. Years later I placed third at the Scottish universities track and field championships. I placed third in Culross too.

The Culross Invitational race logo is derived from the seal of the Burgh. Three birds rest on the Abbey roof at whose door St. Serf stands in prayer. It it shown in white and red on the crest of the primary school and in an altered form stuck to the back of my seat tube, spattered with mud.

The history of the village informs the Invitational in other ways, chiefly in the spirit of arbitrary favour and exclusion. King James VI made Culross a Royal Burgh in 1588s, meaning it could trade overseas. He also granted the Hammerman Guild a monopoly in the production of girdles. These wrought iron cooking plates were used to cook bannocks, the oat cakes which were then the staple food of working people in Scotland. Girdles were essential, demand for them was high, and a monopoly in their supply made the village immensely wealthy until a cheaper cast-iron alternative was invented in Carron near Falkirk from 1760.

All this would horrify free marketeers. But protectionism is back. At the Culross Invitational information is drip fed from a one-man Steering Committee to contestants invited by fiat and vested with no right to contest race directives. One competitor, a local man, was heard to remark at the start line his fear that people from Falkirk had been eating the villagers’ pets and that “I alone can fix this".

The race continued. At lunchtime riders sliced and cleaved wedges from the Grand Cheeseboard then spent the afternoon stitched, cramping, and malnourished from wheels of camembert and brie. There is a reason Tom Pidcock did not stop for a ploughman’s lunch during the Olympic cross-country mountain bike race. It would not have made him go faster.

The field fragmented through the afternoon. Hannah got lost and her third lap extended to 27 kilometres, which did not count. Ben Earle-Wright dropped his baby and belted round in record time (37:58). Emma churned out four laps. Jess and Mehdi made out three, although Mehdi latter required attention at University College London Hospital.

Riders admired the course: the cobbles and burnside, the forest and single track, the gravel, the gentle climbs and the one quick descent. Much of it runs a landscape which had been coal mines (ash from Longannet power station was pumped along the embankment, poured into Valleyfield lagoon to the level of the surrounding land, and capped with topsoil).

Riders did not admire a colossal fallen beech tree brought down by a storm. This bisected the path at the fastest point of the course and caused the field to wheeze together, brakes screeching, as riders stumped off their bikes to squeeze under the trunk.

This obstacle was not ideal, but the course was preferable to making house calls on a folding bike in London. The main thing I have learned doing this, as when two doubled-decker buses converged on me along Oxford Street, is a whiskered sense of what will fit a given space. The red walls moved in and I leapt forwards, catlike, and went clear.

Back on my Genesis Mantle, its huge wheels rolling, I felt by contrast like I was driving a tank, or settling down to work at a partners desk: oak-timbered with decorative mouldings and a red leather surface. Then I remembered the time I lost the front wheel of the desk on a section of greased chickenwire-encased north shore at Glentress. I cracked my helmet and hook of hamate, a bone in the base of my hand – which I discovered a week later when the energy transferred using a garlic press displaced the fracture. The crash also snapped the right brake mechanism and the repair shop only had a white one. Now the desk looks more like a mistreated Dalmatian.

The Genesis has of late grown deeply unreliable. The Irresolute Desk being given now to sudden hub collapse and crank disarticulation. Still, the bicycle is secondary to the rider. Unfortunately at this time the rider is also damaged goods. Something has happened to my right patella. The kneecap, that funny little disc in the quadriceps tendon, has, after forcing my Brompton 180km from London Fields to the Suffolk coast overnight, started swivelling 30º anticlockwise whenever I put it to work. This has given rise to a slight limp and nagging pain following exertion. I can live with the limp, but being unable to run is no fun.

I sought rehabilitation by means of one-legged wall-sits and by ironing perched atop a wobble board. I was determined to race, the Invitational being my Ascot, Boat Race and Mardi Gras combined.

My knee taped and strapped, my scones topped with cream, jam and paracetamol, I stayed out of the big gear. Still my listless year told in the afternoon. The fast group moved away from me and for tracts I rode alone. This was fine, for while cycling is a way to be together, it is also a way to be alone.

Summers earlier in life I rode across the Alps and soaking Dolomites and parched Atlases and sawtoothed Corsica on a steel bike with panniers and friends. Mostly we lived in amity and peace, save for one schoolmate, an intractable human flick knife, who clipped the wing mirror of an oncoming car coming down a pass distracted by a marmot. I suggested he allocate more of his drug money to brake pads and he replied that I had wished him run over. It took the rest of the day to transform our hurt feelings into miles but by nightfall our bicker had passed. Sublimation is powerful.

I have learned more tact. In fact I try not to say anything unless I have something to say. When I do however, it is liable to have a backstory.

Take my shirt. It is bright red cotton with double-underlined font down the long left sleeve and an aeronautic insignia in the centre of the chest. I got it in Houston, Texas, at the Johnson Space Centre. Being there at 16 was the prize of a national science competition, the Scottish Space School. We toured facilities and assembled little rockets. I crashed the shuttle simulator and set up a late winner against the NASA soccer XI. Astronauts invited us for barbecues and we talked and talked to the spacemen and engineers, but mostly to each another – at all hours on any subject. It was special, and so the shirt became special to me. It was already worn by the time I gave it to Amélie 15 years later before I moved to Boston.

Our relationship did not survive. I got the shirt back two years after she left. I put it on. It smelled of her laundry powder and her flat. Like mornings when her cat stood on my chest. Like sitting beside her. Like night. But the shirt was older than all that, older than the effect of its end on me (Wile E. Coyote plugging himself into mains electricity then holding up a Help sign). We cannot live in the past forever or least not all the time. I could not un-fade the wear her care wore the year I was away, and would not. But I could fade the insignia and the text and the weave my own way again, and in so doing might record something new on the tape.

I put it on. The long sleeves were good for the brambles. I did not get scratched. With forty-five minutes on the clock I marked my fifth lap in the ledger, took water and biscuits and bolted out the gate. Rob and Donald and Peter were out of sight. I would need a fast lap to get in under the wire. I asked the old strength to come when called. By the second railway crossing the buttons on the desk were all flashing red: Soviet missiles had arrived in Cuba, the Berlin Wall was up, the Viet Cong had taken Saigon. I was cooked.

The upper reaches of my thighs cramped and my knee which had hurt for a lap and a half now made me feel sick. I called off the search. I turned the bike around. I noticed for the first time how green the world still was. The leaves of grass and fatty buttercups and nettles and brambles and thistles harsh and waving and Culross is named for the 'place of thorns’ and that’s true as ever.

A few years ago I would have forced myself through it. I had wanted to be in the frame. I was not strong enough. I remembered it was my birthday. Then I remembered the other. That one whose knowing had been so much and who soon was to be married in California. Slowing by the trees I smiled for her joy then felt the loss of her again as though it were the first stroke. Then sadness was like a waterlogged football pitch. I saw that the train track, though disused, yet connects Culross to Edinburgh and London and that I might go under the sea to Paris and indirectly to Beijing and south to Shanghai to a cargo ship slow across the Pacific to San Fransisco where I might see her and where we might talk a little while in the sun. This was all mad but the fact of the daydream (in the mind of one who sent her once a postcard from a mountain with only her name and Canadian hometown, and which did not arrive) says all I can of how unlikely it was that we came to know one another at all, and of what she means still.

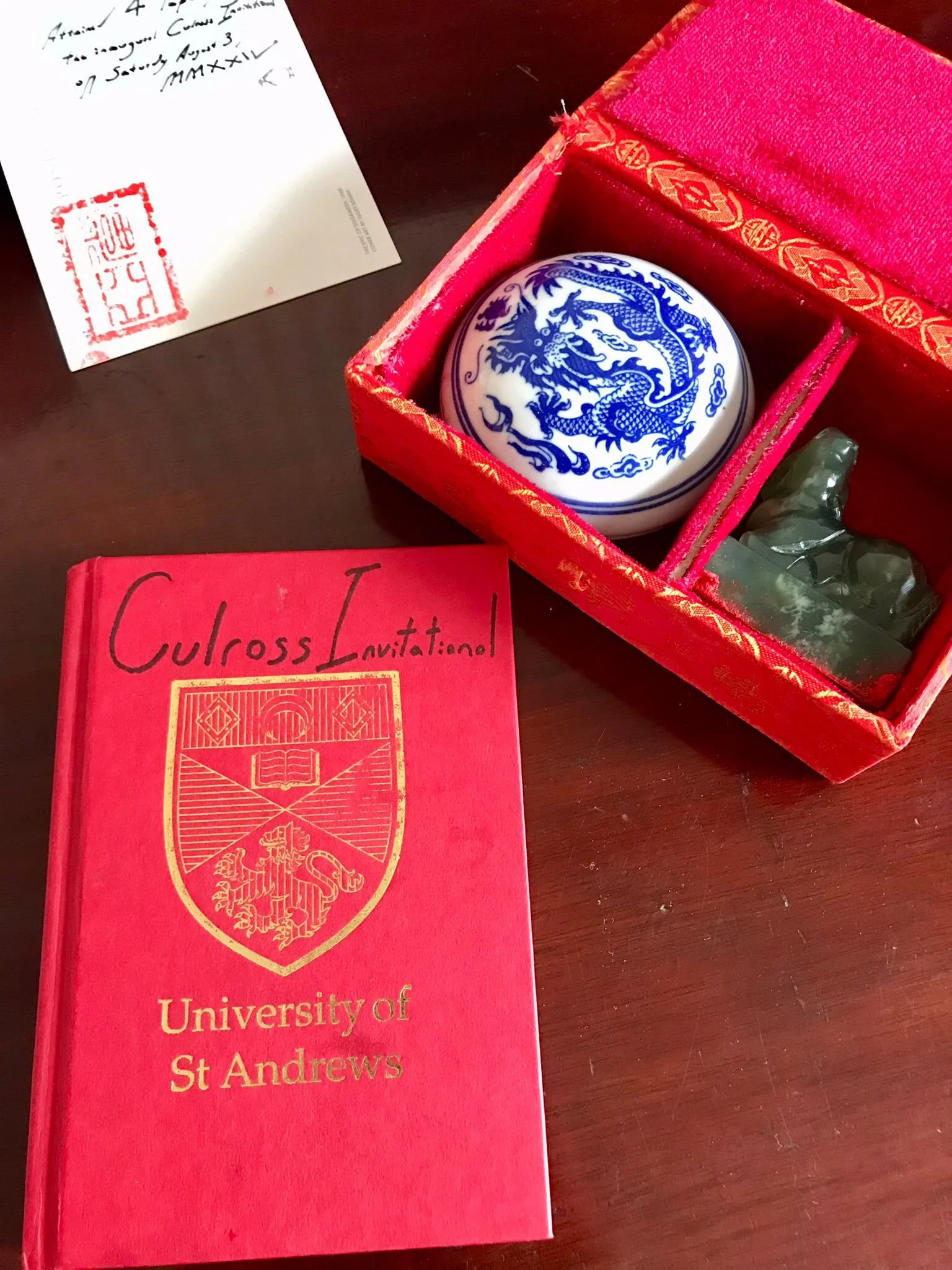

It would not be long before the end. The ledger closed. The nod to other laps, waiting. The change to Nantucket reds, white shirt, knit tie, felt Western hat. The garden party. The food, the sort only my Mother makes. The uncorking and laughter. The certification process: laps recorded on Penguin Classics cover art postcards hallmarked with the official stamp of the Culross Invitational – a jade ram bearing calligraphy pertaining to the Chinese zodiac (finally a use for that) – distributed in accordance with temperament and performance (Ken Munnoch ‘Explosives’, Laura Douglas ‘Mantrap’, Michael Black ‘Men Without Women’). A reading from Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson (“If a man does not make new acquaintances as he advances through life, he will soon find himself left alone”). My laps on the selected W.H. Auden (“Follow, poet, follow right / To the bottom of the night”).

The impossibility of undoing the past. The leaping, ye lame, for joy.