Natural Shrewdness

Published by Singletrack (Print Only)

We were on the wrong side of Glen Feshie and the bridge had washed away. By the look of the gnarled relics it was not a recent event. Should we ford the river, backtrack, or seek another passage further up? We met a party of jolly good chaps off to shoot at something feathered. They warned that it narrowed and deepened upstream. Reviewing the condition of the river, it appeared only moderately deep. We hitched the bikes onto our shoulders and strode into the flow.

The water rose up our thighs. We pressed on over unseen rocks and tried not to slip. It wasn’t too much bother.

For most junior medical staff, life is a series of packing exercises. Like a migratory bird, the season changes and it’s time to go. I returned to the Highlands for a year following a spell in East and West Africa but had accepted a teaching job in London. I had a few spare days of leave and decided to make a journey through the hills in the region of the Great Glen.

Old friends assembled in my attic flat in Inverness. Patrick Olden and Peter Munnoch, with whom I have cycled, camped, run and bickered for half my life. We scoped out a two hundred kilometre loop beginning and ending in Inverness which would incorporate sections of the Great Glen Way and the Kintail-Affric and South Loch Ness trails. This committed us to certain sections where the Ordinance Survey map indicated no marked line. Our feelings about this oscillated between optimism (“in terms of actual bogginess that’s only five or six kilometres…should be fine”) and dread (“a quarter of the trip could be unridable or at least highly unpleasant.”)

The forecast deteriorated. Rain and wind. We went into town to stock up on dry bags. Peter selected his tools: mole grips, tyre levers, spoke tool. He cut a length of rope to keep his rucksack closed and singed the ends in the toaster. Patrick played chess on his phone and looked on derisively.

“You guys are prepping like you’re going into Mogadishu.”

I stowed a few specialty items: face mask, bottle of Balblair, a large ginger cake from my mum.

Peter got us moving.

“Let’s get out on the old dusty trail!”

“Not a lot of dust today Peter, only mud.”

From my front door we joined the Great Glen Way and skirted the wooded shoulder of Dunain hill. The Highland Hill Runners meet here on a Tuesday night. Picture interval track training staged several miles into the woods where track is replaced by a loop of roots, exposed rock, and a home straight pitched at a 45-degree angle. Populate the track with generations of men and women who are sinew and smiles. Keep running until you cannot breathe, think or see. Do it again.

Like hill runners, mountain bikers are impervious to bad weather. Once you’re committed and going, it doesn’t really matter what the weather is doing. You just go.

Underfoot the trail was soft and yielding, like riding through brie. On the high section beyond Craig Dunain we found a strip of single track which was basically a flume. Through flecks of grit which sought and found my eyeballs I saw a frog leaping; green limbs akimbo, splaying wildly to be free.

The film of mud which coated all bikes and bodies were washed clean by the spray from below and the downpour from above. Patrick was dressed in cotton: a salmon t-shirt and heavy sweatshirt.

“I don’t know where my skin ends and the t-shirt begins.”

He wore a tight black plastic shell belonging to his girlfriend.

“Check out this jacket…it does nothing!”

There are sharp switchbacks on the long, narrow descent to Drumnadrochit. Cambered rocks and greasy tree roots are arranged to unseat complacent riders. From Drum we joined the Kintail-Affric way, which moseys through forest and glen to the seaboard on the west coast. We beat a faster track along wide, smooth fireroad to Cannich of Strathglass. There we spent the night in the croft of Hamish Myers and Cara Mackay.

I met him in the doctor’s mess in Raigmore. He was watching videos of sheep.

“Hamish, would you mind turning that down?”

“Sorry, it’s just when they start shearing it gets loud.”

Hamish is one of the medical registrars. He’s also a surfer, shinty player, fiddler, ex-ladies man, and crofter. Once, spotting him deep in conversation outside the high dependency unit, I wandered across expecting to hear conversation about inotropes or a deteriorating patient. Instead he was bartering over cuts of silverside. One of his dexters had been to the abattoir.

We wheeled our bikes into a shed loaded with scythes, surfboards and shinty sticks. He gave us a quick tour before hurrying off to join sheepdog training over Zoom.

Though he had grown up on the croft, he had never specifically intended to return. He trained in Edinburgh and worked in Cornwall and New Zealand before coming back to the Highlands. He bought a flat in Inverness but kept a few animals on his parent’s land – “gateway sheep.” His full transition to life on the croft happened a few years later when his mum and dad moved to Edinburgh.

In winter his day begins at 5.30am. He unhooks the electric fence, lets out the hens (“Good morning Ladies!”), and feeds the rest of the animals: ninety sheep, five cows, a cat, a dog, and three pigs. From there he drives his pickup to Beauly, rides the train to Inverness, and cycles up the hill to the hospital in time for the 9am ward round.

“There’s always more you can do than actually do, especially with a full time job,” he explains.

So it’s a matter of setting realistic goals.

“This year we want to train Taurus to be a proper sheepdog, stop him mucking up the vegetable plot, and make some hay.”

Old machinery throws up endless complications (“The baler is a bit temperamental”) as does the weather. Bad weather seems to be the only thing that ruffles Dr Myers. For him it is the difference between fine bales of hay and mouldy grass.

Rain continued to pour down on the roof of the croft as we showered and changed in the guest rooms. I noticed a framed scrap of brown paper marked in pencil by Messrs Nicoll and Andrews, plasterers, on July 10th, 1948: “We will be dead and forgotten when these walls are pulled down.”

Patrick noted the continuing torrent.

“Just enough to top up the bogs for our arrival.”

He also noted a further problem with his packing.

“I’ve forgotten my trousers.”

He came down to dinner wearing Peter’s swimming trunks.

Over a stew of their own beef and vegetables from their garden we talked shinty, dogs, drug gangs, and classroom mayhem in the Inverness primary school where Cara teaches. By comparison, life on the croft is peaceful. Though it’s not always a dream.

“The reality’s not so glamorous when you’ve got escaped sheep and you’re trying to get to work.”

Hamish had for years been moving, working, journeying. Now he leaves the croft only reluctantly. Aged thirty-two, this is the place he has dedicated himself to.

“This is where I’m going to live until I’m an old man.”

It is one of the old ways of the world. A steady, purposeful, strenuous life.

The following morning we made our way into Glen Affric. I had come this way before. My friend Stuart had suggested an overnight ride from Inverness to Kyle of Lochalsh one Friday in midsummer.

“Set off after work, catch the 6am train home. Easy mountain biking. Head torch sufficient.”

I got home, wolfed a large bowl of meatballs and set out toward the west coast. As evening crept into night riding came to feel like something novel: an activity I’d done almost my whole life, yet in the darkness, somehow different. It would have been magical were it not for the meatballs which sat in my stomach like a curse upon the land.

We stopped for cheese, biscuits, quiche and grapes at Hamish’s. My morale lifted and the sickness passed with a peppermint indigestion tablet and three cups of tea. I felt gathering strength in my limbs as the night wore on and the folds of hilltops appeared in greyscale when you switched off your lights. In the dark your other senses heighten. I heard the rasp and churn of tyres on shingle. Felt the texture of long grass brush my legs. Then the clouds parted and night become as Kerouac had it:

“The evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all the rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in…”

Wrapped in a cocoon of wool, the cold gnawed only a little. We were still hauling our bikes along an unrideable section at the head of the glen at 4am. We spoke barely at all, and never stopped save to grab a handful of trail mix. We had agreed a motto: to keep moving forward, in whatever fashion. Our prospects of catching the morning train seemed to be fading when at last we found an access track and rallied. Then began a wild dawn chase for the train. I called to Stuart.

“It’ll be close but it can be done.”

In the end, twelve hours after departure and with six minutes to spare, we screeched into the station at Kyle and boarded the train. We had crossed the country in the night. I held my arms aloft. Stuart just muttered “If I ever suggest anything like this again, say no.” Then fell asleep.

This time we rode Glen Affric by day and the glories of the wide, lonely space revealed themselves. Yesterday’s storm had inundated the track and we rode through fords and long sections of trail submerged beyond the hubs of our wheels. I chose to relish the spray and thought how amazing it is what a mountain bike can get through if you just keep the wheel facing forward and churn the legs.

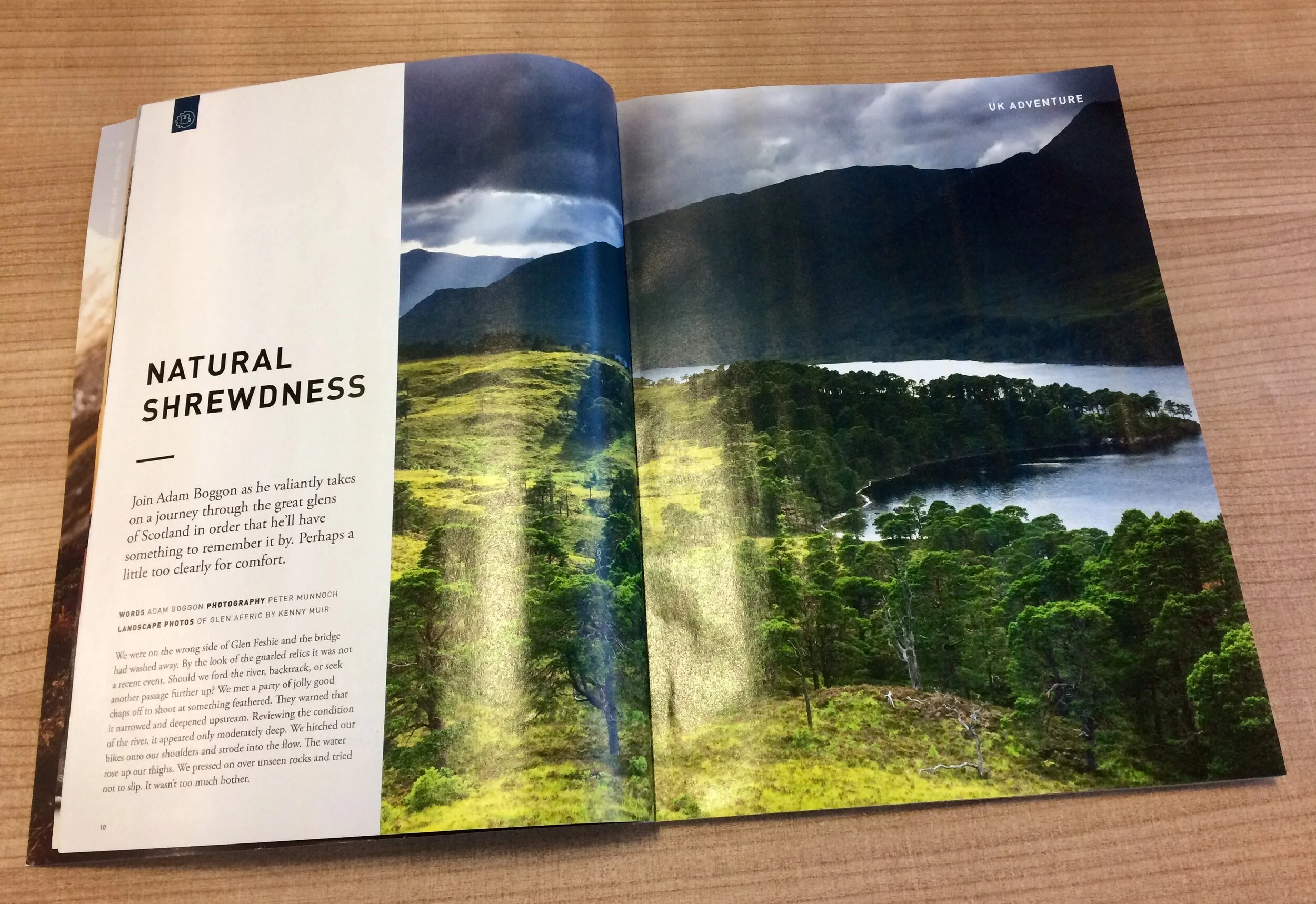

According to The Observer, Affric Lodge may be rented from James Matthews and Pippa Middleton for $16,900 per night. But the glen attracts those of more modest tastes as well. Kenny Muir has been coming here since taking a consultant endocrinologist post in Inverness two years ago. Moonrise, dawn, or solstice – there’s a good chance you’ll find Dr Muir in Glen Affric. His consistency and patience were rewarded in March when he was named Scottish Landscape Photographer of the Year.

When asked about the appeal of the land, Dr Muir is characteristically understated.

“I just like being there. There are so many hidden, quiet places you can go. I nearly proposed to my wife there too, but in the end I sort of fluffed it.”

The rain started again and we hid inside Alltbeithe, Scotland’s remotest youth hostel. We ate cheese wraps and wrung out our garments.

On a winter’s night in 1942, a Wellington bomber crashed into the side of Mullach Fraoch-choire. An engine failure in bad weather on a training flight from Lossiemouth to Tiree. The crew bailed out and all lived, thanks in part to a local man who hung a lantern outside his home for survivors to follow in the dead of night. A few days later, officers from the Ministry of Defence attended the crash site. They buried the ammunition and shredded the wreckage “in case it would be of some use to the enemy should they land at Loch Duich."

Any would-be invader seeking to wrest control of our island chain via this lonely tract would be stymied by a different obstacle: bog. Traversing the lower slopes beyond the crash site, we encountered a prospect disheartening to Patrick Olden.

“That is exactly what I did not want to see. More miscellaneous uphill bog.”

Anticipating a lot of hike-a-bike, I wore high boots. After years of football injuries (stamp, sprain, twist) my ankles offer as much proprioception as a peg leg so need all the support they can get. Alas these proved insufficient.

Stepping forward onto a darker patch, a dank smell wafted up. The bog heaved and sagged like an overloaded trampoline. Then it tore. I sank beyond my waist and began to flail. Conscious of a desire not to wind up installed in the British Museum next to the Lindow Man, I used my bike frame to lever myself out of the swamp. Blanket bog covers a fifth of the Scottish landscape. Peatlands replenish reservoirs, flavour whisky, protect us from floods, nourish sheep and, according to NatureScot, afford “recreation.”

I was happy to escape with my life.

Two and a half hours later we slithered out of the trackless morass down to the Cluanie Inn for cheese on toast and took the road round to Invergarry.

The third day broke sunlit and still, which at this time of year meant one thing: midges. The word itself makes you itch. On the Torridon circuit, they descended like a cloud and sent us skittering at wild pace around the pink sandstone loop. I bathed myself in repellant. Unfortunately Peter chose this moment to overhaul his brake system and we were eaten alive anyway.

I had only been to Invergarry once before. I was there with friends to run the section to Drumnadrochit, though deep snow lay upon the ground and over the thirty miles our pace slackened from trot to limp. We arrived long after dark with teeth chattering so much that I, as my ten year-old cousin Emma likes to say, “sounded like a stapler.”

Now the thaw revealed a strip of rolling, flowing single track through gorse and fern. We diverted at Fort Augustus then peeled off General Wade’s military road at Loch Tarff to begin the South Loch Ness Trail. The land was empty and broad, unpeopled and silent. We moved into it.

For Robert MacFarlane, wilderness is “an expression of independence from human direction.” In an essay for the London Review of Books, Kathleen Jamie railed against what she saw to be an ahistorical fantasy. She pointed out that in this country land is owned, managed, cleared, and hunted upon. It is endlessly contested. Humans strike out from their comfortable homes to “seek out remote places for some spiritual quest,” and Jamie rolls her eyes.

This may be so, and Kathleen Jamie is within her rights to torpedo pomposity on sight, but I wondered if perhaps those who slop around the backcountry should be allowed to derive their small quotient of joy unmolested.

We moved through high ground over gravel, forest track, rooty downhill, hardtop and mud bath. All the while winding towards Inverness and the end of this portion of my life in Scotland.

It had been a peculiar year. In the NHS it is common for life to resemble a screenplay cowritten by Franz Kafka and Joseph Heller. At the beginning of the pandemic my hospital borrowed a large tent from the Red Cross for drive-through screening. A suspected case would drive in, window ajar, and the swab would be taken. The tent blew away in a storm.

At first there was confusion and fear. Then the great rusted hull of the hospital began to turn. Elective procedures were cancelled and medical and surgical admissions combined. Patients were triaged ‘red’ or ‘green’ to separate suspected coronavirus cases from everything else. Cardiac arrest teams carried bum bags containing full sets of PPE. We attended side rooms in full regalia: helmet visor, mask, apron, gloves. The helmets were heavy and made you feel like a medieval knight.

Arrive early morning to make coffee in the doctors’ mess and you hear what’s occurred overnight: interesting cases, problems, any capering. In a small hospital the mess is where you go to learn of chicanery.

“We’ve called the police for assistance with the man who’s barricaded himself inside his room again”…“One of the vascular patients was asking if he could feed his amputated leg to his dog”…“The idea is to make a podcast about bed management. It’ll be called Flow-Rida”…“Mark, those scrubs are fucking massive. You look like a Salvador Dali clock.”

Of course you hear your share of whingeing but for these people you recall the injunction of William Carlos Williams: “If you can bring nothing to this place but your carcass, keep out.”

The mess is just a room: four walls, five sofas, a phone line and a kettle. Hospitals are the same: just beds on wheels, oxygen tubing, scanners and laxatives. What makes them more is the hurrying, arguing, smiling and mending. The patience and speed. The scene unfolds daily, and you can never say for sure what will come. A hospital is the people of the hospital. They draw us back.

The trail dropped to the shore of Loch Ness after a marble-run descent down the Fair Haired Lad’s Pass. This has always been a place of myth. The Loch Ness monster was described by Adomnán as early as 565AD. Apparently it was persuaded to pull Saint Columba’s coracle west on his journey home.

Steve Feltham, a fitter of burglar alarms from Dorset, gave up a settled life to search for it. He moved into a van which had contained a mobile library. His vigil has lasted thirty years. Despite intermittent access to a boat, a microlight, sonography equipment and considerable perseverance, he has yet to record a sighting.

In the 17th century, Coinneach Odhar looked through a ragstone (a pebble with a hole through it) to predict the future. The Brahan Seer augured that someday “ships will sail round the back of Tomnahurich Hill.” The Caledonian Canal permits this today. Alexander Mackenzie published a collection of the prophesies in 1877 and acknowledged that while many were unfulfilled or doubtful, others were “attributable to natural shrewdness.” These included a description of the infidelities of the Earl of Seaforth, an insight for which the Brahan Seer was rewarded by an “untimely death by burning in tar.” Mackenzie’s collection shows some of the ways by which rumours become lore and facts become fancies. This is no surprise. We have always told stories to and of ourselves to render on the world an appearance of sense.

Riding the last stretch through Drumashie Moor I saw dense spiking forests, green and breathing. Banks of gorse, harsh and waving. Water teeming in the creeks. The lean and crest of valley and glen. I thought of all the paths crossing and recrossing the land. From Sorn to Lybster, Flodigarry to Machrihanish. A span of trails like the weave and cast of nerves. Marked by foot of drover, packhorse, pilgrim, soldier. The long, low ways of Scotland.

In the failing light, through the crackle of bracken, I thought of how one life can contain many fine things – even the whole blessing of the earth. Just not all at the same time.

In Loch Farr the peated water leaves a film on your skin. Rhododendrons crowd the lochside beneath the pines. In the body of it you see the rain fall hard from a leaden sky, bouncing and scattering the flat surface. You kick your legs, stretch your arms out, pull through the cold. Know that you will miss this place.

The end came. I pulled the brakes. Left the hospital. Packed a life into a few bags. Walked once more beside the river. Boarded the sleeper train. Saw looping gulls and the top of Craig Dunain. Then the ruckle of land fell behind me – Moray, Cairngorm, Perthshire. Then the tilt and yaw of the carriage. Firm cotton sheets. Then sleep. Then morning. London. Euston Station. New life. Again.