Pilgrim’s Regress

Published by Singletrack (Print): https://singletrackworld.com/shop/category/magazines/

The King sits in Dunfermline toun,

Drinking the blude-red wine,

‘O whare will I get a skeelyskipper,

to sail this ship of mine.’

It’s carved into a post embedded in seventy tonnes of cement wheelbarrowed by villagers over slats to the end of the rebuilt pier in Culross, West Fife, Scotland. That’s where I’m from and where I was going back to.

The quiet coach from King’s Cross contained an enormous toy pirate ship and a noisy six-year old boy. Passengers fumed through pursed lips. At Edinburgh Waverley, a train guard with a tie so long it dangled between his legs.

From the carriage I sent a briefing to Peter Munnoch and my brothers Daniel and Alexander Boggon:

‘Forecast is 15°C and very wet for the Pilgrim Way on Saturday. Distance is 90km. I’ve printed maps’.

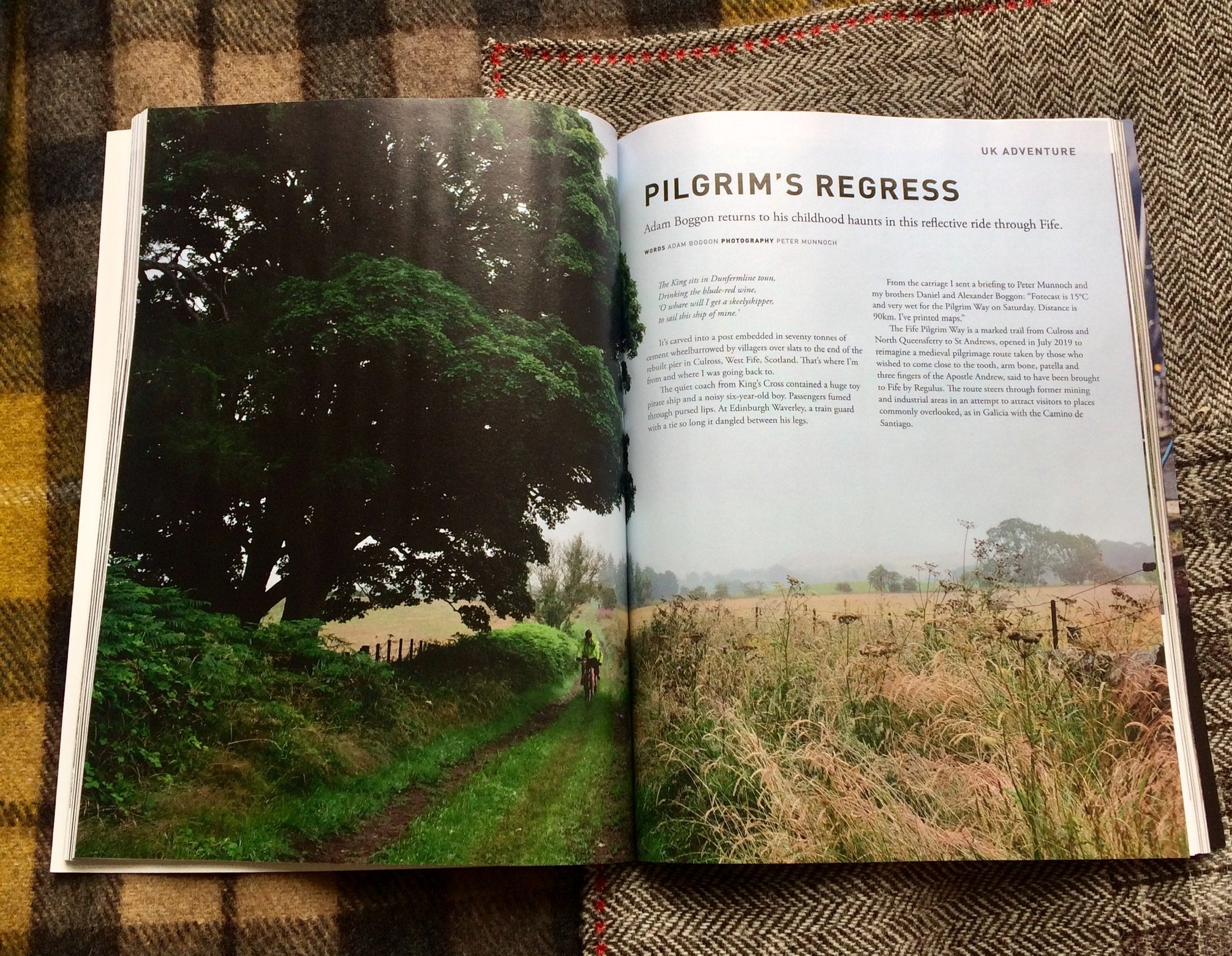

The Fife Pilgrim Way is a marked trail from Culross and North Queensferry to St Andrews, opened in July 2019 to reimagine a medieval pilgrimage route taken by those who wished to come close to the tooth, arm bone, patella and three fingers of the apostle Andrew said to have been brought to Fife by Regulus. The route steers through former mining and industrial areas in an attempt to attract visitors to places commonly overlooked, as in Galicia with the Camino de Santiago.

*

I stirred water into my porridge from a tiny kettle in Agnes Blackadder Hall, St Andrews. Peter used his penknife to hack a plastic cup into a usable spoon. Outside long sea-rollers came in under the mist.

Thin soaking rain worked into us across the Swilken bridge to the Cathedral - closed now due to concerns about falling masonry. Daniel lost his front wheel on the cobbles on College Street and almost ended in a pile.

I sat on a slim bench flush to the tall plate glass window and bottle green doorframe of Taste. It is small inside, and many hours I have sat eavesdropping, peering, interjecting and casting aspersions. For now the chairs are upside down and you have to wait for your coffee under an awning.

We ate fudge doughnuts from Fisher & Donaldson and strapped one to the rear rack for my dad. He’d eaten four rhubarb tarts from the same bakery the previous night and had asked us to bring him something else. At least we know how we’ll administer his concealed medication should the time ever come.

We left St Andrews by Lades Brae and passed Drumcarrow hill. A narrow section beside the Duke’s golf course was corded with slick roots and we rode gingerly to avoid punching trees. We paused while Peter attempted to repair his bike with zinc oxide tape - he’d dislocated the ball and socket joint of his rear brake lever when he fell into a gully on his last day out.

My dealings with Peter began at the egg-throwing competition at the Culross Gala when we were children. Contestants toss an egg back and forth across a widening gap. When it smashes, you lose. We smuggled ours into the Munnoch’s cottage and set it on the stove. But boiled eggs still crack: we were found out.

We made our way into the Howe of Fife by farm track, built path, waist-high meadow grass and bean field. Peter was the first to topple having failed to spot a drainage ditch. Partially digested custard ferreted its way back up my oesophagus and I discovered why crème pâtissière is not considered a mainstay of sports nutrition. By Ceres the Fisher & Donaldson box had largely disintegrated and custard was herniating out in clots and drooling onto Daniel’s leg.

Much can be said against Daniel Boggon: stubborn, abrupt, cantankerous, and a reckless driver. Yet this must be said in extenuation: he is a snappy dresser. Bedecked in a red merino top, white cotton socks, a pair of ‘90s Irish road team bib shorts, black plimsoles and a white helmet which had at some point been partially melted. He speaks almost exclusively in brief assertions (‘that gin is poison’; ‘I want sunscreen’). His girlfriend Courtney describes his aesthetic as ‘erratic, colourful and aggressive’. He is the Worcester sauce in a Bloody Mary. A sort of thrift shop Gaddafi.

We were together in part to mark my 30th birthday. I’d been troubled only once before by the thought of growing old. I was nine and walking on the embankment in Culross with Julie Geyer, already ten. The things you should know, should have become. I shuddered. Double figures.

Strange what it does to you - this sand, air, stone, mortar, grass. The way in which a small town where you have been young brims over with ghosts. I could see the waves of students pressing through the streets to listen to Noam Chomsky speak in Younger Hall. Medical students in the old Bute stamping the floor to a crescendo at the behest of the Dean. One face most of all. Her dark hair as she stepped away, disappearing into the underground beyond my sight.

Looking down, my old Genesis Mantle seemed more mud than bike. A dent in the top tube where someone had tried to spring it from a U-lock one night in Newington. The black paint worn thin with scrapes from Innerleithen greywacke, Torridonian sandstone, Gambian clay. All paint lashed from the chainstay. It hadn’t been the same since a period of immersion in the River Ness: seizing, shrieking, shuddering. A new chain, brake pads and a lot of oil put it right enough. It’s a hardy thing.

We rode southwest through low lying farmland by Craigrothie where my parents dance reels of terrible complexity: Postie’s Jig, Cadgers in the Canongate, Bratach Bàna. Scottish people like ceilidh dancing because it is vigorous and highly structured. There is no call for flair or potentially exposing expression. Learn the steps, bow and curtsy, enact. It is better that way.

After a short road section though Kennoway, we cut into a long stretch of single track beside open fields. Beads of rain on clover and thistles by drystone walls where arcing swallows built their nests.

In Riverside Park, Glenrothes, there is a labyrinth. In the myth the first was made by Daedalus in Crete to keep the Minotaur. Later they were built for Christians to walk and permit those who could not visit the Holy Land to experience something of a pilgrim journey. These labyrinths wend and weave but are without wrong turns or dead ends. You follow the line to the centre and back again. The prayer is with the body and the feet.

In his 288-page companion to the route Ian Bradley, professor of cultural and spiritual history at the University of St Andrews, encourages us to see the mind of a medieval pilgrim as something quite different from our own: a place overwhelmed by fear of ‘death, judgement, Hell and damnation.’

Churches were often decorated with murals like the one described by J.L. Carr in A Month in the Country as the Big Treatment - a Judgement:

‘With Christ in Majesty at its apex, the falling curves nicely separating the smug souls of the Righteous trooping off-stage north into Paradise, from the Damned dropping (normally head-first) into the bonfire'.

The question was: what must I do to be saved? Part of the answer was deemed to lie in penitence: atoning for misdemeanours to obtain God’s forgiveness. The Church prescribed penalties for sins which might diminish the likelihood of the pit. If this was worth a punt, it made sense that an optimal pilgrimage should be long, perilous, uncomfortable, and ideally flea-ridden. More pain now, less pain later.

Yet by the 16th-century the blossoming apparatus of indulgences and prescribed penance came to be seen by Protestants as deeply suspect. Admittance to Heaven could not be bought with hard currency and suffering like a Dunfermline Athletic season ticket. With the Reformation, pilgrimage in Scotland effectively ceased.

Now pilgrimage routes are back on the map, even in this unimaginatively secular time where it is more generally held that heaven and hell are places we make for each other here on the earth. Broken people still embark on pilgrimages, Bradley points out:

‘To seek forgiveness for sins and come to terms with failings…carrying their hurts, guilt, unresolved tensions, unease and fears’.

Stopping for lunch in Glenrothes where we were joined by Courtney I reached for wedges; Alexander reached for a fistful of painkillers. He’d pranged his knee and was struggling. Shortly after snaffling his analgesics he started going on about moose knuckles in relation to Daniel’s bib shorts. It was time to go.

My family do a good line in forbearance. Eight weeks after a total knee replacement my mum went snowshoeing in the Ochil hills. Recently she has taken to eating bullet-shaped turmeric and ginger capsules which she refers to as her ‘horse pills’. When death comes for her she is liable to offer him a fishcake then poke him in the eye.

From Glenrothes we continued towards Kinglassie, Kelty, Kingseat and Lochore Meadows. The land here was once covered over with Caledonian pine, birch, rowan, beech and oak. Later, the mines came and West Fife was dotted over with bings. These are landscaped now, so you’d hardly know there were once fifty collieries operational here.

A 1606 law allowed mine owners to ‘apprehend vagabonds and sturdy beggars and put them into labour.’ Miners worked in ‘mining servitude’ - or slavery - until 1799 when it was decreed that ‘all bound colliers, shall be free from their servitude.’

Conditions improved only slowly. One account describes a miner in the 1850s scraping and howking in seams underground by the phosphorescent glow of decaying fish-heads deep where the air was too foul for tallow to burn. Infants of Fife were grimly greeted:

‘Ye’ve come into a cauld warl’ noo’.

Before the First World War, twenty thousand miners laboured in West Fife. The last deep mine closed in 2002.

Rounding Loch Ore, I was starting to flag. As I waited for the second wind, I looked across to Alexander. His face was pale, laced with pain.

Daniel barked encouragement.

‘Be the knee!’

‘Go to the centre of the pain!’

The day ran on. The riding was smooth over well-built paths. Through woodland and rough ground which must once have been a spoil heap we climbed over Kingseat and down into Dunfermline, long the burial place of the monarchs of Scotland. Robert the Bruce is here, save for his heart which is interred in Melrose after being taken on crusade. Andrew Carnegie was born here the son of a weaver. He moved to Pittsburgh, became a steel magnate and the richest man in the world.

In later years Dunfermline slipped from preeminence. The 1845 New Statistical Account registered a concerned report of ‘drunken brawls, and acts of wanton mischief, committed during the night by persons under the excitement of spiritual liquors, have, for a few years past, been frequent and outrageous’.

This remains more or less the final word on Dunfermline nightlife.

We rode behind East End Park and down to the Abbey and Pittencrieff Park, its sixty-acres bought by Carnegie for the people of the town. Then out again towards Culross - we were on the home straight now.

Fife was known as the pilgrim kingdom. Thousands traversed the county to venerate St Margaret, St Serf, St Mungo and St Andrew. It was believed that being close to bits of old saint might permit the faithful to snaffle a portion of their sanctity.

St Serf is said to have set up a monastery in Culross. According to the Vita Sancti Servana, a 13th Century Irish manuscript, Serf studied divinity in Alexandria, was for seven years Pope, wandered across the Alps, debated the Devil at Dysart, slew a dragon, and threw his staff across the width of the River Forth - a little over four kilometres.

This is hagiography - an embellished form of biography intended to ham up the reputation of ecclesiastical figures. Though you wonder if a contemporary Serf would struggle to impress a 21st Century Fifer: did ye, aye?

My second wind arrived as we battered through fields and woodland west of Dunfermline. Not far off is Devilla forest, where in July the blaeberries come up in thickets and your fingers are stained for days. Close too is Kirkton Farm, where I worked on the harvester. To the north are the Ochil hills, at the foot of which lies a Japanese garden maintained in the 1920s by Shinzaburo Matsuo, who wore wide-pleat trousers, white spats, golf stockings, Kimono and a velour hat, and was sometimes mistaken for the Emperor.

I went to Queen Anne High School in Dunfermline. Beside the school a rank of red buses fourteen deep. On the top deck you worked your way back as the years passed. Those in the last row set the tone: with fist, taunt, jest. Once we raced the nine miles home by bicycle after school: piling helter-skelter out at the bell, haring down past the Broomhead flats, lungs burning through Crossford, Cairneyhill, Torryburn - the string of villages between Dunfermline and Culross. We beat the bus with five minutes to spare and waited to gloat outside the post office eating foot-long jelly snakes.

The shop is gone now. Of the boys I knew then, three are dead: one by illness, one by accident, one by suicide.

I thought of a Fife folk song, and of the paths behind, and of the half-imagined past.

‘As the tide shrinks back into its womb,

I hope the empty shells and bones of your stories

will litter and clutter the shore

and I hope that when I find them I remember

how they danced

and the racket they made

when they were alive’.

Special thanks to Professor Ian Bradley, Peter Munnoch, Courtney Barnard, Ben Goulter (BenGoulter.com), Robbie Clarke of Domino Records, and HMS Ginafore, who granted permission to use her original lyrics from ‘And The Racket They Made’ – which I heard first in a recording by King Creosote on a CD belonging to Innes Cameron.